Charging up the batteries

To us the point seems clear: skilling up for the battery revolution spreads well beyond the gigafactory walls.

In September 2021 the Faraday Institution, working with the UK’s High Value Manufacturing (HVM) Catapult and the University of Warwick Manufacturing Group (WMG) published a key report on Electrification Skills. The report estimated that the UK would need to hire an additional 20,000 people for the planned UK gigafactories, with another 50,000 needed in the associated material supply chain. By June 2022 these estimates had increased to 35,000 and 65,000 respectively.

GigaFactory: generic term referring to "...facilities that produce batteries for electric vehicles on a large scale". The term was initially used by the electric car manufacturer Tesla, Inc. to refer to their battery manufacturing facilities. The concept's success has led to the genericization of the term.

Source: Wikipedia

Image of Nissan Leaf battery: CleanTechnica

According to Faraday, 41 gigafactories are either in planning or are operational across Western Europe. Three of these are in the UK: Envision AESC (Automotive Energy Supply Corporation) has one already operational with an expansion planned in Sunderland; plus, despite enduring rather shaky times, the Britishvolt venture in Blyth1. The North East will soon be glowing in the dark, we fancy.

The current Envision AESC plant employs 440 people and with expansion this could rise to 4,500. According to Envision, the expansion will bring enough capacity to make batteries for 100,000 cars annually – around 35GWh of battery power. That’s a lot of gigawatts and hours but still, to take full advantage of manufacturing ‘at scale’ we learn that a gigafactory needs to be churning out around 100GWh worth. Meanwhile, the Advanced Propulsion Centre estimates the UK will need 98GWh of battery capacity to support its domestic car industry by 2030 while, going back to the Faraday reports, we may need as many as ten UK gigafactories will be needed by 2040. Big numbers indeed.

The real trigger that will drive the expansion of UK gigafactories will be Jaguar Land Rover’s developing EV plans. But also, lurking significantly in the background, there are the decisions around the European roll-outs from the major Chinese companies like BYD, which is both a major car manufacturer and battery maker. Whatever, global battery demand is expected to multiply 6 or 7 times by 2032, with the key driver, as ever, being the electrification of vehicles.

But there’s much more to gigafactories than the battery assembly done by the factories themselves. There’s also the supply chain, where we learn, for example, that the plastic laminate holding the electrodes apart is currently imported from Japan. There’s also the core material - lithium - and here we see major investments being made either directly or in long term contracts of, typically, 10 years. And we’re going to need a load of that plus other key materials - the world is going to need at least 384 new mines for graphite, lithium, nickel and cobalt by 2035. With around 25% of global EV battery supply coming from South Korea with firms like SK On, LG and Samsung, presumably much of the product from these new holes in Mother Earth will be travelling over there.

We also have lithium refinery investment circling the UK with both Green Lithium and Altilium planning plants on Teesside. Looks like at least one of the freeports we reported on in our recent post might be able to take advantage of its proximity to a key UK hub for refining and recycling lithium.

Like other critical commodities these days, security of supply is high on the agenda. For lithium hydroxide, for example, we see a move away from cheaper competition as auto makers seek to reduce their dependence on China. Livent Chemicals, with a manufacturing plant in North Carolina, is one company gaining from this move, no doubt aided by the new funding being made available in the USA under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, 2021.

And so it goes on. The outcome of all this activity, as one might expect, is the plummeting cost of EV battery costs. According to BloombergNEF, manufacturing costs have dropped from $1,200 per kWh in 2010 to around $100 per kWh today, the net result being that the inflection point in Europe - where EVs will be cheaper than fossil-fuel vehicles - is predicted by round 2026.

Source: BNEF (2021), Hitting the EV Inflection Point

When looking back from 2030, we will see a revolutionary change to a greener industry. Yet despite the rapid pace of this change, it will be incremental year on year, building on and changing the skills base of our current workforce.

And change won’t stop in 2030.

Source: The Opportunity for a National Electrification Skills Framework and Forum, 2021

While, understandably, the major focus right now (and, we guess, for the foreseeable future) is on batteries for EVs and the gigafactories they’re made in, that doesn’t mean that the demand for batteries for use elsewhere is insignificant. Power back-up and uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) in industry and the built environment; electric mobility for non-EV road, rail and air; laptops, mobiles, and consumer electronic goods; grid energy balancing, to name but a few. And, in skills terms, it’s not all about simply building batteries: there are the skills for installing, integrating, optimising, maintaining and, of course, the whole circular economy stuff around reusing, repurposing and – if all else fails – recycling.

The Electrification Skills report we mentioned at the head of our post describes the emerging battery skills landscape quite neatly:

Source: Faraday/HVM Catapult/WMG

At the level of the individual job, we’re seeing these up-, re- and new skills emerging all around: installing and commissioning; financing and insuring; testing and validation; design and development; sourcing and supply; management and optimisation; materials research; mining. Then there are the applications: within the electricity infrastructure; military use; integration with solar systems; circular economy; swap and upload, and so on. The point is clear: the need for battery expertise and skills spread well beyond the gigafactory walls.

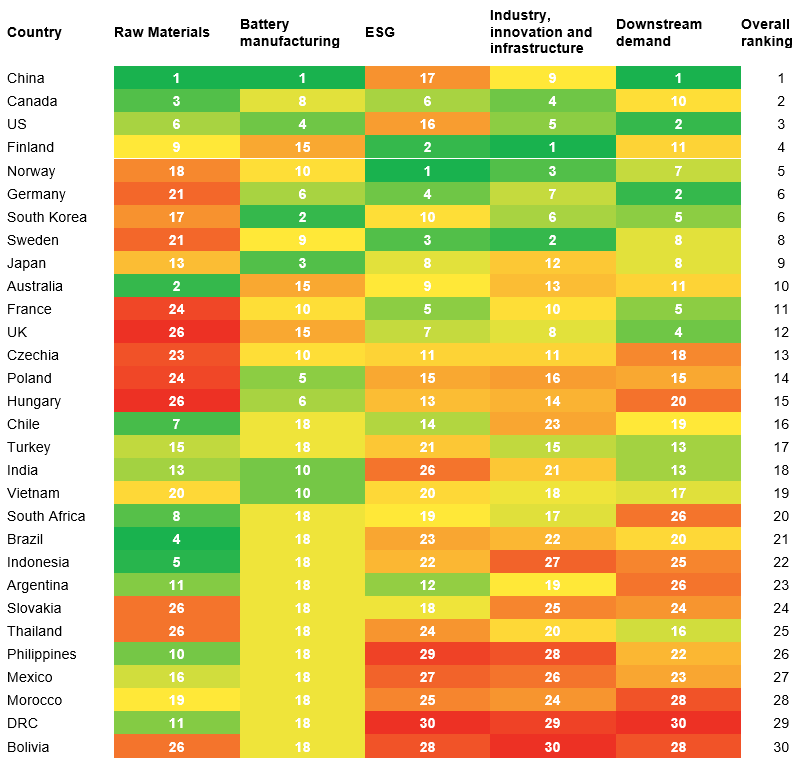

And as the chart below, borrowed once again from BloombergNEF shows, while the UK comes some way down the list in battery manufacturing (and are even lower in raw materials), and lags behind the likes of Canada, Finland, Norway, Sweden and Germany in both 3I (industry, innovation and infrastructure) and ESG (environmental, social, and corporate governance) considerations for batteries, we are 4th in the world for battery demand, lagging only (though admittedly by a pretty long chalk) China, the US and Germany2.

So we’d better get cracking with these gigafactories, then.

Source: BNEF

Sponsor The Green Edge

To keep The Green Edge free to subscribers, we’re asking for sponsorship. Click on the button below for further details. Thank you.

The Government has a key role, of course, and has been very active in supporting Britishvolt. But this has been challenged very recently. Having a consistent and long-term national battery strategy for the UK is critical.

Putting this in context, the two world-leading countries are China (567GWh in 2022 / 1,569GWh by 2025 / 3,135 GWh by 2030) and the USA (47GWh in 2022 / 172 by 2025 / 634 GWh by 2030).