A walk on the (re)wild side

Opinions are mixed on rewilding. We've just visited a couple of projects in Scotland to see them for ourselves.

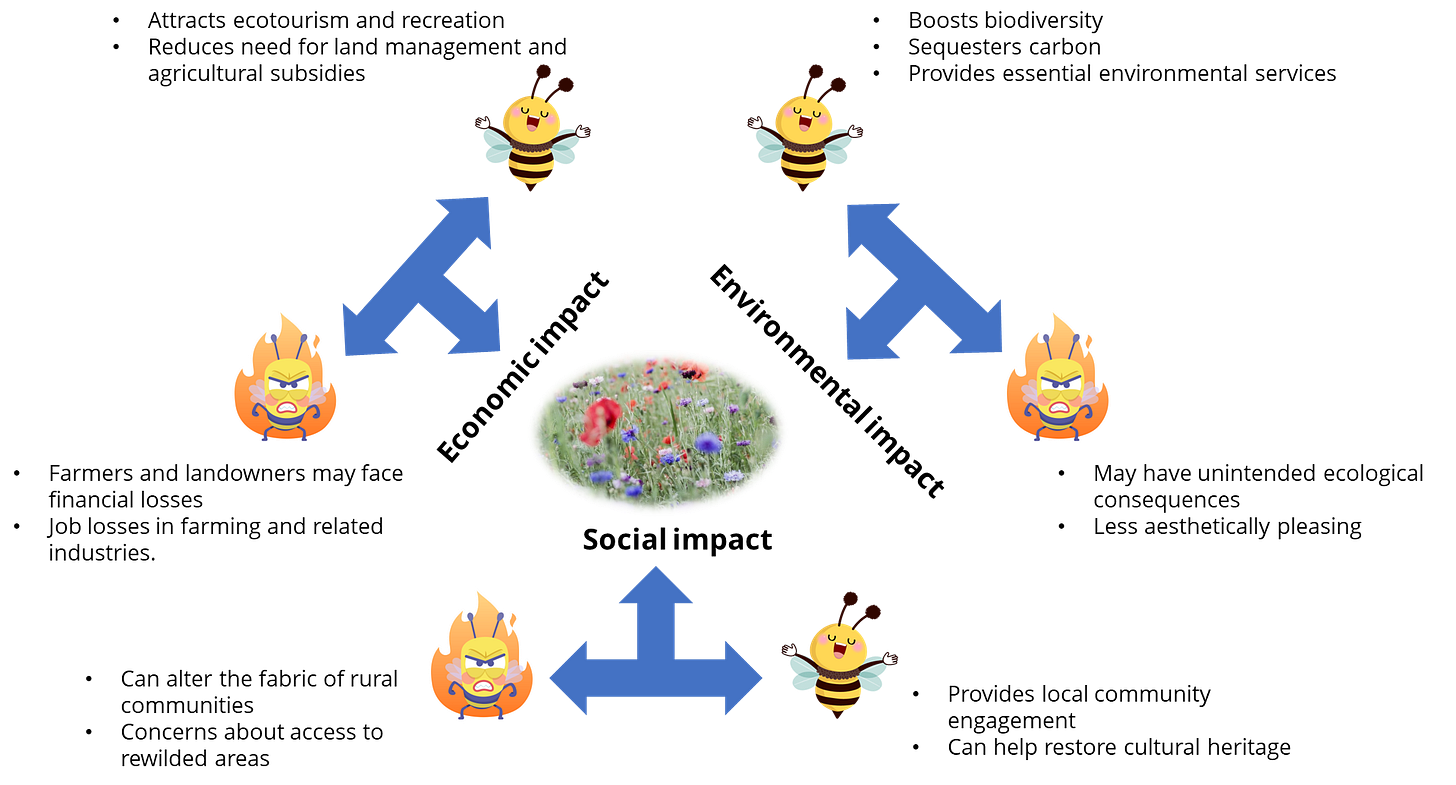

Rewilding, the process of restoring landscapes to their natural, unmanaged state, is a topic of considerable debate, both here and abroad. The conflicts in opinion largely stem from differing perspectives on its environmental, economic, and social impacts.

Image: TGE

Examples here in the UK: New Statesman described the Knepp Estate Project in West Sussex as ‘a microcosm of the tensions that plague rural politics’; while opinions to the reintroduction of the Eurasian lynx in Scotland range from its virtue as a shy and elusive wild pussycat to a wicked beast that’s going to eat all the sheep.

While the debate is complex and multifaceted, we have no doubt that successful rewilding projects need careful planning, community involvement, and ongoing dialogue between stakeholders. So, to that end, we were delighted recently to be able to visit two such schemes in Scotland, to see what they look like first-hand, to learn a bit more about what they entail, and perhaps even to further our own opinions one way or t’other about whether rewilding is a good thing.

Here's where we went…

Trees for Life (Dundreggan Estate, Inverness)

Rewilding is about an holistic approach. It is about looking at the land at a landscape scale. Source: Trees for Life.

Putting it simply, Trees for Life is planting trees. One and a half million of them so far. High fencing keeps the deer off and, from what we saw, the folks there are growing trees for transplanting with a deal of enthusiasm. At Dundreggan, it’s added a rewilding centre which houses a lecture theatre and events space, plus an accommodation block – and at around 145 quid a night on the likes of booking.com, don’t think of this as just a bunch of bleak portacabins.

Image: Trees for Life

In our opinion the Centre is a good move. It means they can engage in a wider education programme with local communities and volunteers, and refine their methods. Rewilding a previously open piece of peatland takes time. The Trees for Life charity has been going since 1993, buying the Dundreggan Estate in 2008. Alongside the return of swathes of the mighty Scots Pine (we can feel a song coming on here), previously rare species like aspen, mountain top willows and birches are starting to be re-established. There’s even a chance of seeing wild boars and feral pigs scavenging on local crops and frightening the horses – oh dear, there’s that conflict again.

Our opinion: we agree with Trees for Life’s own assessment of itself as bold, collaborative and pragmatic. The charity employs nearly 80 staff, plus it has worked with around 5,000 volunteers over the years. All profits from the Rewilding Centre are reinvested in the Trees for Life charity, going directly to support rewilding. Revenue from carbon credits from parts of the Dundreggan Estate go to support two community charities, the West Glenmoriston Community Company and the Glenmoriston Improvement Group. And the Dundreggan Centre – which, by the way, employs nearly 30 staff – was built with a successful crowdfunding bond raising effort with Triodos Bank, raising £2mn in 48 hours. We chatted with the Centre’s staff and came away impressed: here is a rewilding project going about its work without a loud flourish or wild claims, truly embedded into the local community (perhaps with the slight exception of the wild boars and the feral pigs).

Highlands Rewilding

Consisting of three estates1 – Bunloit in Invervess-shire, Beldorney in Aberdeenshire and Tayvallich (Taigh a' Bhealaich) in Argyll – Highlands Rewilding is, in many ways, very different to Trees for Life. Rather than a collective effort built up over many years, Highland Rewilding was founded just five years ago by a single individual, driven by a vision of rewilding and a well-voiced concern about climate change.

Dr Jeremy Leggett is social energy entrepreneur, founder of Solarcentury (now part of Statkraft) and SolarAid, and author of five books on climate change. In mid-2019, his purchase of Bunloit from the Vestey family was featured in Country Life and the 500-hectare estate is at the core of Jeremy’s rewilding vision. Over the past few years he’s built a team of around 30 highly-qualified staff to manage the rewilding of Bunloit along with the more recently-acquired Beldorney and Tayvallich estates, which together have added a further 1,700 hectares.

In contrast to Trees for Life, we might say that Highlands Rewilding has raised funds aggressively rather than pragmatically, landing large chunks of funding from equity sales (£11mn) and bonds (£5.6mn), with a further £12mn in loans from the UK Infrastructure Bank. This gives Highlands Rewilding a somewhat different set of operating parameters to Trees for Life: with this weight of investment comes the expectations and pressures of a normal commercial business.

So, how does rewilding work in a commercialised world? Through creation and enhancement of natural capital, of course, and its value in the – for many – hazy worlds of carbon offsetting, compliance markets both statutory and voluntary, and monetisation of ecosystem services beyond pure carbon sequestration, like water purification, flood control, biodiversity support and the somewhat throwaway-line lure of eco-tourism. Here on The Green Edge, we know a little bit about this world, having been involved in earlier days – around 15 years ago now – in understanding the value satellite data might bring to the measurement of large tranches of natural capital, and we also know and how complicated it can all get when things like crypto make their way into the mix.

That’s not to say we have any kind of inside track on whether Highlands Rewilding are doing any of this (although they may be for all we know). But we do know that it’s done a series of baselining studies to measure – which it will then monitor – its tradeable specific natural capital gains, and it has produced three Natural Capital Reports, the latest of which describes its progress in peatland restoration, rainforest regeneration, pond creation, targeted deer control, and regenerative agriculture.

Image: TGE from Highlands Rewilding

Our opinion: Here we were left with the impression that there is great potential, but we also heard a range of negative comments about engagement and one-way consultation (your view should be our view), which might explain why local expectations are dampened. It’s always disappointing to see the damage temporary roads make when taking out inappropriate forests, and the time it will take for recovery and restoration to take place. But, with the large funds raised, the pressure is on for this scheme to show real returns in all areas.

What did we learn?

As the blisters start to fade after a few days tramping through forests and across peatlands, and as our chats with some of the good folk up there sink in to our collective noggins, we’re left with a few points to share:

Bring everyone along on the ride

All land-based schemes for rewilding rely on massive levels of co-operation and collaboration. This is not just about employees and volunteers; it also calls for multiple landowners to agree joint agendas as the actions of one landowner impacts their neighbours. There are lots of other so-called ‘stakeholders’ – individuals and groups – that have to align their own ideas and agendas. Nature, after all, has no clue about political, legal, economic, community and other human-societal borders.

Build a shop window

Engaging people helps many to see and understand what is going on, and what is being achieved. Something like Dunreggan’s Rewilding Centre is a cute move: it demonstrates to all who want to see that that there’s some good strategic thinking going on and that complex projects like this can be delivered.

Incorporate opportunity

Both of the schemes we saw have generated jobs in relatively remote rural locations. Granted, many of these are for highly qualified professionals, but there are also some ideal entry roles. Rewilding projects can also show what the countryside and all forms of agriculture have to offer in terms of climate change adaptation and mitigation, and they can bring new income streams to economically challenges areas.

When it comes to rewilding, opinions differ. But, on the whole, most people would agree that enhancing or restoring biodiversity is a good thing; that healthy ecosystems are better able to withstand and recover from environmental stresses like climate change, natural disasters, and human impacts; that we need to take carbon out of the atmosphere (even if we struggle to spell sequestration); and that there is some ethical and moral value in preserving and restoring nature for its own sake.

On our trip to Scotland, where we saw the most potential for conflict was with the major renewable projects we saw being developed. Lots of wind farms along the GB Divide, new pylons abound. We’re also watching Ed Milliband go gung-ho on Great British Energy – solar, hydro and nuclear might all be seen as the right thing to do to ‘make Scotland Britain’s energy capital’ but remember that rewilding projects might also be trying to establish themselves for the longer term in some of the same spaces. The next chapter of Britain’s political future could prove to be a testing time for many of them.

We visited Bunloit.