Thinking about Systems Thinking

Systems thinking is an essential skill for Net Zero. But getting it into schools curricula is going to be difficult with the current approach.

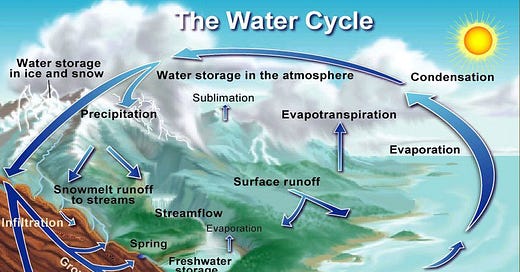

For those of us who remember the posters of the Water Cycle from our schooldays, the images of the sun shining over the sea, the rain clouds over the mountains and the rivers flowing down to the land and lakes below gave us one of our first experiences of systems thinking. The systems thinking skills included in building, understanding and managing models – often complex ones like industrial processes or socio-technical systems – are widely believed to be critical in handling the complexity facing the world in the coming decades.

Systems thinking skills complement the ‘harder’ skills associated with fields like systems engineering and systems dynamics. They recognise the complexity of multi-stakeholder, multi-disciplinary situations and are most useful in dealing with the levels of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA) that are now the norm in many industries, businesses and environments.

But while systems thinking is regularly talked about in policy-making circles, with the UK Government, OECD, WEF and others featuring it in many publications and reports1, the opportunities for embedding it into UK school curricula seem to be limited, due to a focus on assessment by terminal exams.

The Green Edge had a conversation recently with Professors Andy Lane of the Open University and Ian Jenkinson of Liverpool John Moores University, both of whom identify systems thinking skills as a gap in the current UK education system. We wanted to understand more about the gaps and how systems thinking might be embedded in TVET and school education to prepare young people for the complexity of their world, including the drive towards Net Zero. We discuss this with Andy and Ian in the full article, which you can find, together with a video of the conversation, by subscribing to the Green Edge newsletter.

In the frenzy of enquiry that will inevitably follow the pandemic, we feel that one of the key debates will be around the relative values of reductionist and systemic approaches, and the relative weighting given by governments to each side in determining the most appropriate responses at any given time. While the UK Government, for example, initially stressed that it was being led by the science, the complexities and uncertainties of the many moving parts – political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental – have been experienced in real time by everyone within a short timeframe. The resulting case studies, when they are eventually written, will be fascinating to read.

The UK Government even has a blog on it – see https://systemsthinking.blog.gov.uk/