We’ve commented many times and in as many words that craft1 skills are essential to the green transition – or, as we’re increasingly viewing it, the restoration of a sustainable planet.

Whatever we may call it, many aspects of the transition involve the installation, maintenance, and repair of renewable energy technologies and energy-efficient heating and cooling systems. Likewise, tradespeople are integral to improving the energy efficiency of buildings and infrastructure: tasks like retrofitting insulation and upgrading doors and windows all contribute to energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Craft skills are vital in constructing green buildings and tradesfolk who understand eco-friendly construction materials and techniques are in high demand to meet green building standards. We could keep swimming in the green skills mainstream – along the lanes of green transport, nature conservation and so on – but we’re not saying anything new here.

Meanwhile, we see projections of increasing numbers of skilled craftspeople being needed in what some may consider to be the less obvious areas of the transition – although by no means less obvious to those involved. Like waste and resource management where, for example, the Chartered Institution of Wastes Management (CIWM) predicts that the much-needed transition of the repair economy from being largely volunteer-driven towards becoming ‘industrialised’2 could create as many as 140,000 new UK roles between now and 2040.

But, while it may not be accurate to say that they’re going entirely out of fashion, we do see several trends and factors influencing the perception and demand (or, perhaps the perception of demand) for craft skills. The increasing use of automation and technology in various industries; changing workforce demographics, with many skilled craftspeople getting older and not being replaced with new entrants; craft-based education and training programs facing challenges in terms of funding and support; a perception (still!) that A-levels and university are the only worthwhile way to go; and a general perception that – despite the sterling efforts of some – technician and craft professions are less prestigious or financially rewarding compared to careers like those in (yawn) business administration.

So, given the situation, here’s a question that might seem a little uncomfortable – and, we’re sure, in some quarters at least, downright unpopular – to ask: is it occupations we need, or skills?

Immediately, we can anticipate being off IfATE’s Christmas Card list. Since the Richards Review advocated in 2012 that ‘we must…set a few clear standards: preferably one per occupation, which delineates…what it means to be fully competent in that occupation’, and the Sainsbury Review in 2016 tramlined those ‘few’ occupations into the 15 routes we now find in IfATE’s occupational maps, we’ve had a situation which invites spirited debate over whether critical sets of skills – like, for example, those we now see being needed for the green transition – should be seen as being exclusive to occupations, or whether it’s better to define them as clusters of skills around which ‘green’ jobs can be built.

So, here’s what we’re asking: what are the implications of adopting one approach over the other? Further, where do the two approaches lead as regards the green transition and the individuals involved?

Let us examine the various options in a little more detail. First, we must acknowledge that many trade jobs can only be done by people fully competent, and most probably qualified, in whole occupations. The Sainsbury Review made a pretty good fist of identifying some of the main ones within the occupational routes it put forward in 2016: bricklayers and carpenters in Construction; chefs, butchers and bakers in Catering; farmers in Agriculture; and so on. After all, with no slight whatsoever intended, we wouldn’t want a house to be rewired by a brickie (unless he/she/they is also fully qualified as a sparky, of course).

But then we have what we might call the restricted occupation approach. This is where a subset of tasks belonging to certain occupations are boxed up and people are specifically trained to work in that box. This might work for well-defined sets of activities with high degrees of predictability and risks that can be identified and managed. One example of this could be EV charger installation in one or more settings – domestic, workplace, public, say – although in this example we do need to be mindful of the need to manage the risk of dangerous installations.

Next, we have the adjacent occupation approach. This is where some trades extend into a Venn diagram of tasks and skills with others. Mechanical trades into building trades for retrofitting, plumbers into some of the electrical work required for heat pumps (and vice versa), solar installers into battery systems work, perhaps. We might even see in this approach the potential for cross-skilled ‘units’, like we see in the advertising industry with copyrighters and creatives teaming up, or in software development with pair programming, where teams self-organise in overlapping and, in some cases, interchangeable ways around the job in hand and hand-shaking between tasks is less rigid. This can be good for developing the less experienced team members too.

Of course, these blurrings of the edges would need a deal of careful management. Where critical skills are shared across traditional occupation boundaries, standards and quality management need to be thorough, particularly where health and safety is involved. Then there’s the consideration of the levels of training or competence appropriate to each task or task box. Bootcamp? Or via intermediate apprenticeship of the type we see for Dual Fuel Smart Meter Installers, perhaps?

There’s also the question of ‘trainability’: how to identify individuals most likely to rapidly acquire the necessary competence standards and to understand the boundaries of the task(s) they are competent to do? This implies some form of entry assessment and, logically and to prevent a huge backlog of assessments waiting to be done, we might look for employers to make these assessments as part of their assurance that standards of competence exist across their workforces in line with the products and services they provide.

This competent employer idea also needs managing. Which organisations are best placed to oversee and manage the process of skilling up for the green transition without prejudice and self-interest? And how do we avoid having the big uglies dominate proceedings and thereby control supply and pricing?

Seems like we might be laying out more obstacles than pathways here. But, in our minds some lateral thinking needs to be done by someone, and it needs to be done pretty sharpish. Perhaps no more so than in the case of electricians of all flavours3. Depending on who we read, the numbers vary, but the general picture is of supply going down while demand goes up. Some estimates talk about there being something like 420,000 qualified electricians across the UK, but a recent report done for the Electrical Contractors’ Association (ECA) places that number at less than 300,000, with a big reduction of approaching one-fifth being seen since – and no doubt significantly influenced by - Brexit. Some sources also point to retirement rates of perhaps 17,000 or so each year for the next few years at least.

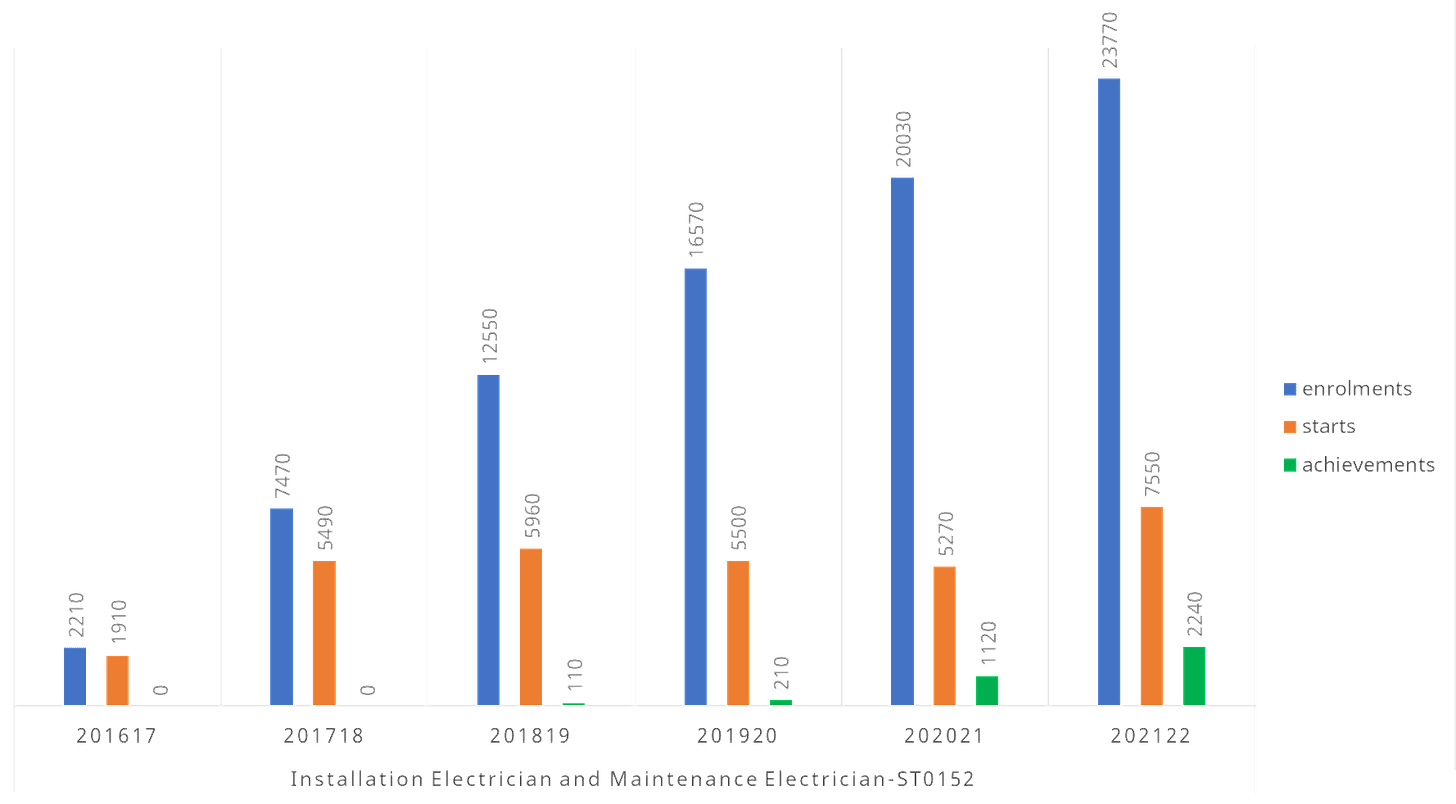

Meanwhile, there are lots of sources of demand: the Construction industry, for example, is saying it needs 104,000 new electricians by 2032. This demand alone dwarfs the supply we see in HM Gov’s apprenticeship enrolments, starts and – most significantly – achievements data.

Image: TGE from data HM Gov.

Now, we’re well aware that the debate about electricians v electrical skills is a thorny one and is one we leave to authorities much more well-versed in the issues and nuances. We also know the electrician trade is heavily regulated by standards, industry licences, international standards like ISO (of which we see much related to heat pumps, heat exchangers, air filtration and ventilation, EV charging, building design and so on), plus of course the particular occupation and apprenticeship standards.

But our question remains a simple one. Who will provide the electrical skills we need for the green transition if we can’t make enough electricians?

We trust our readers will forgive us for using the traditional terms ‘craft’ and ‘trade’ in relation to the skills and occupations we write about in this post. Our respect is deep for the professionals we are describing thus.

We’ll be writing more on this in future Green Edge posts.

IfATE recognises four types of electrician: Installation and Maintenance; Highways; Marine; and the new Domestic Electrician standard. All are Level 3. According to HM Gov data, numbers of apprentices going through the Highway and Marine routes are very small compared to the other two.

Thanks David. In this post we were seeking to capture the directions of travel/approaches we are seeing emerge and describing them. Where there is a large upskilling/reskilling requirement the state invariably plays a key role in funding nationwide programmes. The role of 'experts' is also necessary though when it comes to defining standards and qualifications as these are key parts of the infrastructure of any functioning labour market. Happy to discuss.

Good point Debbie - suggest we pick-up on this when we speak soon.