Keeping Green Warm 2: The Sequel

Who owns the solutions for sustainability? Governments, corporations, technology, or us?

In our previous post on the EU’s green politics and the recent setbacks faced by environmental parties, we highlighted the complex landscape of climate policy in Europe. Further contemplating that particular post simply underlined the point we’ve been making for what seems like a long time: that the responsibility for owning and instigating the solutions we need for a sustainable world shouldn’t just lie with governments and business, and their tendency to fixate on technology to get us out of the mess. Arguably it should lie, ultimately, with us as individuals.

Of course, governments do play a critical role in climate policy, but their track records are, to be kind to them in the utmost, mixed. In many instances, the very institutions meant to drive change have fallen way short. For example, across the EU from Portugal to Poland to Greece, farmers have protested against bans on fertilizer use, a policy aimed at reducing environmental harm. These protests underscore the tension between environmental regulations and agricultural productivity. Even worse, poorly implemented policies, such as the fertilizer ban in Sri Lanka that led to severe food shortages, have had disastrous consequences.

Closer to home, the banjaxing of the Scottish coalition was at least partly caused by the Scottish National Party (SNP) wriggling – as it seems to on a pretty regular basis – this time on its climate policies, upsetting the Greens no end and highlighting a big disconnect and lack of cohesive strategy for sustainability north of the border.

Governments have also been criticised for their inconsistent actions. For instance, many European countries subsidised fossil fuel prices when they spiked, undermining their commitments to green energy. Additionally, Germany’s shift away from nuclear power, increasing its dependency on Russian gas and even turning back to brown coal, illustrates the complexities and contradictions in energy policy.

Alongside government incompetence, one of the most significant barriers to effective climate action is the perceived hypocrisy of the corporations. They play a crucial role, but their performance has been inconsistent. Companies like Unilever, Bank of America, and Shell are backing away from climate targets, partly due to regulatory challenges and insufficient government support. Unilever’s plastic usage highlights the gap between corporate sustainability goals and their actual practices.

Moreover, some businesses may see carbon taxes as a cost of doing business rather than an impetus for change. Paying the tax without adjusting their operations undermines the effectiveness of carbon pricing as a tool for reducing emissions. Encouraging businesses to invest in sustainable practices requires a combination of regulatory pressure and incentives

To overcome these barriers, transparency and accountability are paramount. Governments and corporations must be held to their commitments, and their actions must align with their rhetoric. Public engagement and participation in policy-making can also enhance trust and ensure that policies reflect the needs and values of communities.

Moving to technology, how often do we hear our own Government banging on about technological innovation as the key to solving climate change? Green tech, blue tech, hydrogen in rainbow hues and a wonderful glossary of terms await the uninitiated. But technology alone cannot solve the problem. The infrastructure needed to support these innovations, such as an updated and resilient electric grid, is often lacking. Businesses struggle to access green electricity due to the slow pace of grid investment.

Furthermore, human rights issues in the supply chain for critical minerals, essential for technologies like EV batteries, pose ethical dilemmas. Ensuring that the transition to green technology does not perpetuate exploitation or environmental degradation is crucial.

So, given the big state government attitudes that seem to be proliferating even further into our post-pandemic world, backed by the onward march of technology as the great green hope, how can we possibly contribute to the sustainability cause as mere individuals? Well, in the rare warm days we might see in this otherwise unseasonable summer, a walk along (m)any of Britain’s crowded seafronts and beaches shows the significant role that could be played by many through lifestyle changes like altering diets and reducing consumption. However, motivating widespread behavioural change is challenging. Overcoming cynicism and doubt requires positive reinforcement and demonstrating the tangible benefits of sustainable living.

Small actions, when multiplied across populations, can have significant impacts. For instance, reducing food waste, choosing sustainable products, and supporting green businesses contribute to a larger shift towards sustainability. Yet, these individual actions must be part of a broader systemic change to be truly effective.

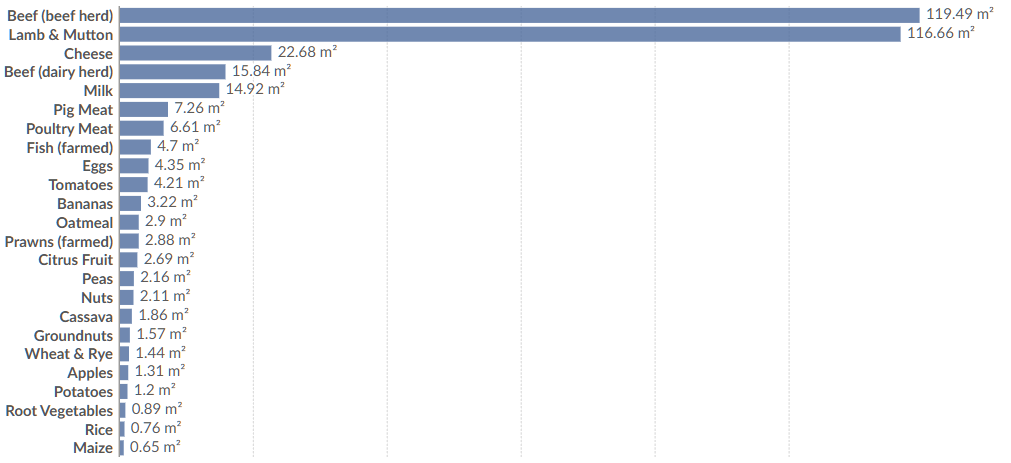

Transitioning to a green economy involves significant economic shifts. Consumers must be willing to change their purchasing habits, which can impact various industries. For instance, a shift towards sustainable diets could massively change the land profiles of agriculture and food production. Reducing fast fashion – perhaps even replacing it with ‘slow’ fashion – could have huge impacts on textile and water resources. Such changes are necessary but must be managed to minimise economic disruption.

Land use of foods per 1,000 kilocalories. Source: Our World in Data

Promoting the economic benefits of the green transition, such as job creation in renewable energy sectors and long-term cost savings, can help garner broader support. And, as we’ve written many times of The Green Edge, policies that facilitate retraining and education for workers transitioning from high-carbon industries to green jobs are also essential.

The path to effective climate action requires collaboration between governments, technology developers, corporations, and individuals. Each has a role to play, and their efforts must be coordinated and mutually reinforcing.

Governments need to enact and enforce robust climate policies, invest in infrastructure, and provide incentives for sustainable practices. They must also engage with the public and ensure that policies are socially and economically just.

Technological innovation must continue to drive progress, supported by investment in infrastructure and ethical supply chains. Businesses must align their operations with sustainability goals, seeing carbon taxes not just as a cost but as a driver for innovation.

Individuals can contribute through sustainable lifestyle choices, but these actions must be part of a larger systemic change. Public awareness campaigns and education can help foster a culture of sustainability.

Ultimately, the path to sustainability requires a multifaceted approach that addresses economic, social, and environmental dimensions. We all have our part to play.