Just a few transitional thoughts…

Just Transition (JT) is going to feature more and more in our green vocabulary as time goes on. We've been taking a look.

For one reason and another, we’ve been thinking a fair bit about the Just Transition (JT) here recently on The Green Edge. Its meaning, its ramifications, even the extent to which it is a ‘thing’.

JT is a thing, of course. The preamble to the Paris Agreement “[takes] into account the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities”. It could be argued that the pandemic gave JT a kick, and the archives from the more recent COPs contain plenty of pledges committing to its implementation globally. Such as this one that “recognise[s] that all countries must benefit from the opportunities offered by sustainable and just transitions.”

We read with interest, therefore, in an estimable recent publication from the Skills and Net Zero Expert Advisory Group commissioned by the Climate Change Committee that:

“…there is a significant risk that the skilled workforce required to mitigate and adapt to climate change in some countries, in particular those in the global south, is itself undermined by such ‘skills importing’ for domestic climate action in other nations.”

Source: CCC

It seems to us there’s something in the nature of concentric circles around the scopes of JT, or at least how it might be regarded for execution purposes. This may even be reflected in the various definitions being adopted. Business in the Community (BITC), for example gives us this:

“A just transition ensures a fair and inclusive journey to a net-zero, resilient future where people and nature thrive. Businesses must design this future with diverse stakeholders; create economic opportunities and equip people to access them and actively regenerate communities and nature”.

Source: BITC

BITC goes on to “urge business, Government and diverse stakeholders to investigate, co-create and activate solutions with us, making fundamental changes to how the UK does business to secure a future for us all”.

All good for business here in the UK, then. But what about if we look outwards into the world and see what, say, the UN thinks?

Well, the UN tells us that definitions differ, but with widespread recognition of the importance of context-specific analysis and strategies. It goes on to say that “just transition refers generally to strategies, policies or measures to ensure no one is left behind or pushed behind in the transition to low-carbon and environmentally sustainable economies and societies”. The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a bit more specific, giving us guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all – all linked to the Decent Work Agenda – and telling us that JT is all about “greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities and leaving no one behind”.

Picking a couple of JT cherries from around the UK, we also see different lenses being applied. For example, another recent publication from the CCC on the Net Zero Workforce looks at ethnic, gender and age demographics among sectors, finding that…

“…people aged over 40, those who identify as men and those who identify as white work in more emissions-intensive sectors on average. In contrast, people aged under 40, those who identify as women and those who identify as ethnic minorities tend to work in less emissions-intensive sectors.

“In several sectors that are expected to phase down or redirect, people aged over 55, those who identify as men, and those who identify as white, are disproportionally represented. Older workers, who are particularly represented in farming and oil and gas, may need tailored support to transition to alternative low-carbon sectors”.

Source: CCC

… while Scotland’s Draft Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan adds a regional view…

A Just Transition for Energy: Regional and National Opportunities. Image: Scottish Government.

When we look at other countries, we find some deeper JT dives. For example, a review made in 2021 of public policies to assist German coal communities in transition found a number of lessons to be learned from previous policy-making, including that of “giving municipal governments more financial and administrative autonomy [to] design, implement, and finance projects needed for the transition, reducing problems of coordination among different policy levels”. No doubt similar lessons could be learned here from the major industrial restructuring in the past across the UK manufacturing base, impacting sectors like steel, coal and textiles, and giving rise to mechanisms like resettlement schemes from some of the the big players - like ICI, Shell and British Steel - to help workers adjust.

But here’s something that seems pretty clear. With the US chucking something like 370 billion dollars into its green economy via the Inflation Reduction Act and with the European Green Deal budget running to around a trillion euros, a shedload of companies in the States and Europe are going to need a shedload of extra people. And where education systems – particularly, we feel, Further Education – can not supply enough home workers, then they’ll need to come in from abroad. Hence, the quote from the CCC’s Net Zero Expert Advisory Group we gave at the top of this post could even be somewhat of an understatement. And that could well be a threat to the wider – and global – principles of JT.

One litmus initiative we feel is worth keeping an eye on is Germany’s agreement with India to import trained technicians for its solar programme. The driver is clear: Germany’s solar energy targets for the second half of this decade means that each year it will need to install three times more solar kit than it added in 2022. This gives Germany a problem, especially since we read that the country has a huge skill shortage, pretty much across the board and including thousands of vocational training vacancies.

Enter stage left (looking south, at least) trained solar PV technicians from India’s Suryamitra skill development programme. Operating since around 2015 by India’s National Institute of Solar Energy (N.I.S.E), the programme has produced around 51,000 ‘suryamitra’ solar PV installers, trained under India’s Skill Council for Green Jobs (SCGJ) model curriculum and qualified against a raft of Indian green National Occupational Standards (NOS). Suryamitra was established to support India’s solar programme1, but since some sources have reported that Suryamitra technicians may be struggling to find work after graduation, then we might assume a fair proportion of them may find a trip to Germany attractive.

To make it all formal and (presumably) Schengen-compliant, the agreement has been struck between the German Solar Industry Association (BSW) and the SCGJ, under the umbrella of the snappily-titled ‘Hand-in-Hand for International Talents’ programme, one branch of Germany’s new Skilled Immigration Act that’s already been finding recruits for the German electronics, IT and gastronomy sectors from Vietnam and Brazil, as well as India.

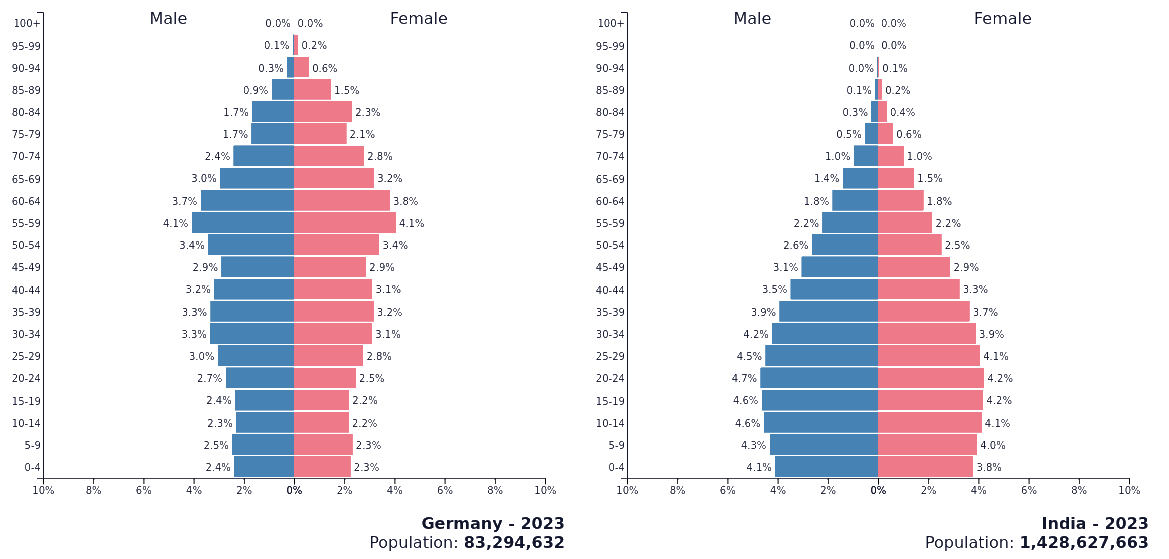

But would a migration of skilled solar technicians from India to Germany prove detrimental to India’s own solar efforts? Under the Global Skills Partnership model developed by the Center for Global Development, it shouldn’t. Instead, it should address all the advantages a bilateral agreement like this stands for – not least, the imbalance between the population pyramids of the two countries.

Source: PopulationPyramid.net

This is but a short foray into the world of the just transition and many of our readers may point out dimensions that we haven’t considered in this short post. Indeed, please do - we’re always keen to learn more. But one key takeaway for us seems to be this: at whatever level we look at JT, it involves potential movements of large numbers of people. Movements between jobs and occupations; movements between sectors and industries; movements between regions and countries. And wherever movements need to take place, the intended beneficiaries of these movements – from the smallest companies to the largest nations – had better try to fulfil their needs from within before going out to market to fill the gaps. Because those markets are going to be fiercely competitive and, taking the example of Germany and solar, latecomers may well find that others have stolen a march.

According to India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) India stands 4th in solar PV deployment across the globe as of end of 2021, and has calculated that the Country’s solar potential of about 748 GW (ie. over ten times currently installed) assuming that 3% of the waste land area is covered by Solar PV modules.

Very true Philip, when I lived in the North East I was involved in one major restructuring at ICI Petrochemicals at Wilton where we tried to ensure the individual and their community were not negatively impacted by 4000 people leaving the site. Our Resettlement Group was well supported, and pension funds were buoyant. Totally agree, the coal, shipbuilding and steel industries suffered badly along with their workers and communities, and it is vital that as the pace of the adjustment of the UK workforce builds-up momentum with the transition to net zero, we need support for upskilling, reskilling and career changes. To make this a reality we need effective transition plans for specific sectors and communities. For many in the energy intensive and extraction industries they have skills very relevant to delivering net zero, and we must ensure their skills are well used as the UK workforce needs every pair of hands over the next 5-10 years.

"Older workers, who are particularly represented in farming and oil and gas, may need tailored support to transition to alternative low-carbon sectors”. This reminds me of the Thatcher era when the needs (economically, socially and culturally) of coalminers were pretty much ignored in the rush to change. It's vital for societal cohesion that we achieve a just transition as well as reparations for those communities affected by but not contributing towards climate change.