Problem Framing the Essdeegee

We've been thinking about responsible consumption and production - that's SDG 12 if anyone's counting.

Image: TGE adapted from UN

For reasons that should become apparent over the next few months, The Green Edge has been taking more than a passing interest in SDG 12, the United Nations’ sustainable development goal exhorting the world – particularly the developed, capitalist one – to be responsible about its consumption and production. And, with the additional thinking time we’ve been afforded over the last couple of weeks while our posts have been admirably donated by our guest writers Luke McCarthy on local councils taking the green skills lead and Tim Jackson on Community Energy, we’ve been pondering this: how can we apply the much-vaunted ‘skills for sustainability’ we read so much about to a problem such as this?

In our hearts, we feel SDG 12 is probably one of the biggest and difficult-est essdeegees of them all. Certainly they’re all important, but in light of criticism from some quarters that the goals place too much emphasis on development and growth rather than advocating for a more radical transformation of society towards a sustainable and equitable status quo, we do tend to agree with some commentators that sticking overconsumption down at number 12 of 17 can be seen as an indication that the goals are, perhaps, too numerous and too vague1. Particularly so, in our view, when we examine the rather woolly SDG 12 infographic that tells us, among other things, that 62 countries – plus the EU – have introduced 485 policies for sustainable consumption and production shifts. Oh, well that’s alright then.

Are we, then, proposing an alternative? Of course not. But we are thinking that a good avenue to explore might be to look at how we can apply some of the skills we write about regularly here on The Green Edge to break down the mega-problem of overconsumption into addressable and, hopefully in time at least, solvable chunks.

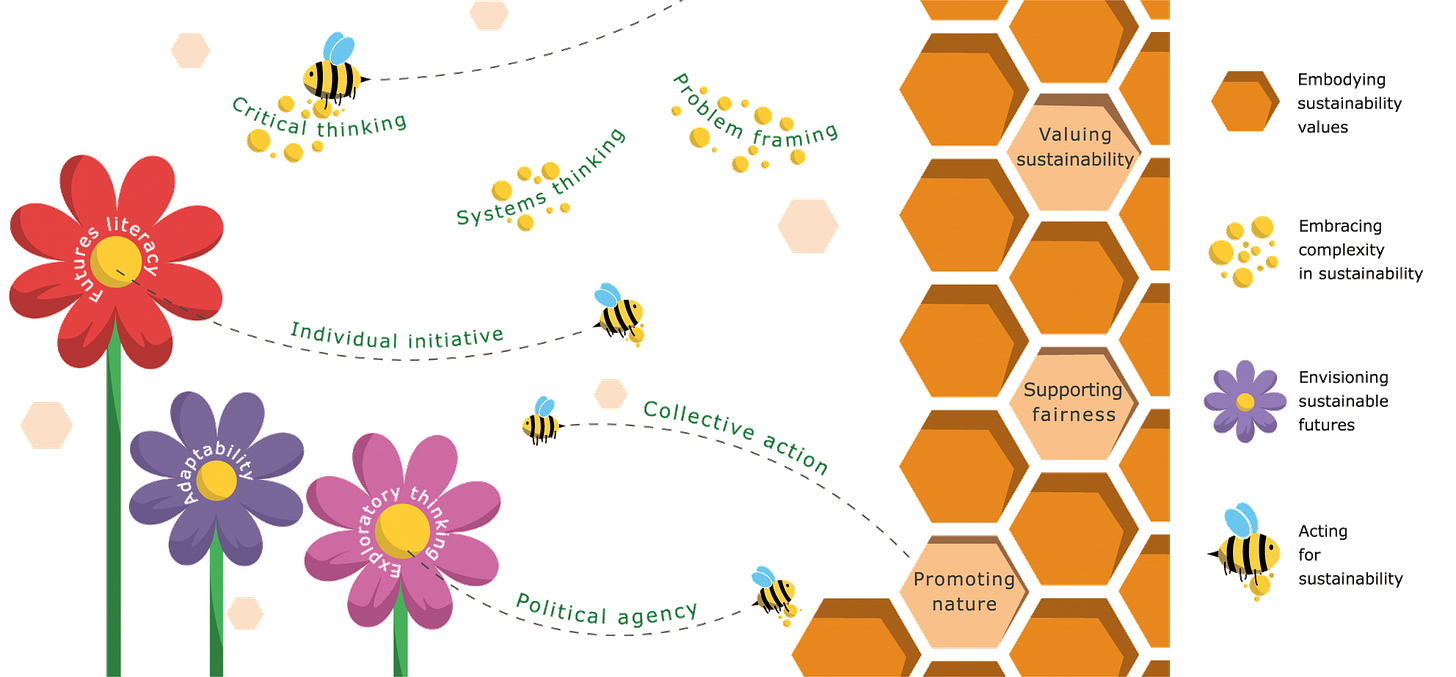

GreenComp conceptual framework. Image: EU.

What skills are we talking about here? Let’s start with two from the European sustainability competence framework, GreenComp: Systems Thinking and Problem Framing.

Intuitively, installing the mindsets needed across all levels of a society like Britain’s for responsible consumption and production is a big systems problem. It needs a holistic approach – starting perhaps, with the ‘growth at all costs’ mantra we hear right across the political spectrum – to joining the dots between all the various social, economic, and environmental factors. Along the way, of course, SDG 12 does help, by pointing to the big associated themes like reducing waste generation, promoting resource efficiency, and encouraging sustainable lifestyles.

Beyond the systems thinking approach, though, there comes the immense task of framing the problems around overconsumption in a way that the low-hanging fruit might be identified, along with the problems that could be addressed in the shorter or longer terms through behavioural changes, technology, policy interventions or a range of other approaches.

So, as a starting point for our problem framing, what might we see as the problem domains giving rise to excessive consumption and production? Well, there’s the consumerism culture, of course, where societies equate possessions and material consumption with success and happiness. Then there’s the capitalist growth mantra we mentioned earlier. Alongside that, we have the potential for overexploitation of finite resources such as water, land, minerals, and fossil fuels. There’s the problem of linear rather than circular production and consumption models, perhaps exacerbated by inefficient urban planning prioritising convenience and short-term cost savings. And, despite the policies and regulations, poor enforcement may still allowing businesses to externalise their environmental and social impacts, instead of internalising them as they should.

These are all big problems to frame and solve, although here on The Green Edge we’re guardedly confident that they’ll get sorted out over time. Put it this way – they have to.

But one problem domain we see as potentially low-hanging fruit is public awareness, and this plays very much into one of our 2024 themes, hearts and minds. In our everyday conversations, we find many people remain unaware of the environmental and social impacts of their consumption choices. Why is this? Limited access to information and education on sustainable consumption practices is certainly a factor, while greenwashing still remains a ‘thing’ (our link is given without comment on any of the entities called out therein).

Providing better access to education on sustainable consumption – perhaps through a build up of MOOCs on the subject – and reduction in greenwashing by continued naming and shaming, might be relatively easy problems to solve. But what may prove a little more tricky is the disconnect between individual consumption choices and their broader societal and environmental consequences. Complex global supply chains might have something to do with that: multiple stages of production, transportation, and distribution may result in consumers not having visibility or awareness of the environmental and social impacts associated with the entire lifecycle of products they purchase. Prioritisation of short-term convenience and affordability over long-term sustainability may be another factor: our repair economy post a few months ago noted how the marked uptick in coffee maker purchases during Covid subsequently led to more than a few ending up on the tip due a return to the coffee shops, difficulty in finding spares, general unrepairability, or perhaps all of the above2.

Another contributor to a solving the disconnect might be this: in its How to build a Net Zero society report, published early last year but perhaps not receiving the widespread notice it deserved, the UK’s Behavioural Insights Team nudged out the view that one of the keys may well be in the ‘midstream’ – that is, the individual’s immediate physical, social, economic and digital ‘choice environment’. It went on:

To focus on ‘behaviour’ is not to imply individuals have the greatest burden of responsibility. An evidence-based and sophisticated understanding of behaviour reveals the interplay between individuals making choices (downstream), within choice environments that currently tend to nudge them towards unsustainable consumption (midstream), which exist as they do because of a system of flawed commercial incentives, regulation and institutional leadership (upstream).

Source: Behavioural Insights Unit, 2023

In other words, the ‘architects’ of our daily choices – supermarkets, online retailers and so on – need to make sustainable choices easier, more available, cheaper (!), more socially acceptable, or even the default choice to take people more effortlessly in that direction.

Something for us to look at more closely over the next few months. In the meantime, here’s a little mindmap we put together with our first cut on the problem domains and subproblems around SDG 12, with our assessment of the relative ease (from green = lowest difficulty to red = highest) each one might be to solve (click on the image to view as png).

In total, the 17 SDGs are fitted into 5 pillars and have 169 targets and 232 indicators. Seems to us that’s a pretty hefty set of KPIs.

Just while we’re on the subject of Repair Cafés, we note that there are now around 3,000 of them in the UK. This has to say something, we feel.