Mind the Gap

In the spaghetti of England's skills system, there are some big holes. The biggest one seems to be that nobody really owns it.

Since the Second World War, the ‘ownership’ of work in Britain – and the requisite skills in the population to do it – can be seen as a process of dilution, deviation and, dare we say, dabbling. And devolution, of course, to the point where we can’t talk about ‘UK skills and employment’, but rather need to look at the systems developing among the devolved administrations as being separate – and different – to England.

Anyway, back to the amateur history. After growing like topsy during WWII under Ernest Bevin in the war coalition, allocating people into the fighting forces and administering the various reserved occupations like (our grandfathers) the miners, the Ministry of Labour and National Service dropped the ‘National Service’ moniker immediately after the war and carried on until around 1959, playing a central role in shaping labour policy and supporting the workforce during the post-war reconstruction era.

Fast forward to 1968, we then got the Department of Employment. Times had changed by then, of course, and after being formed under Harold Wilson, it then wended its way through to 1995, taking in the 1970s and the three-day week, the Thatcher era and the completion of the transformation of our grandfathers’ bold occupation from reserved- to ex-, and all the fun and games involved in transforming Britain from a manufacturing powerhouse to a service economy, before being disbanded in 1995 under John Major.

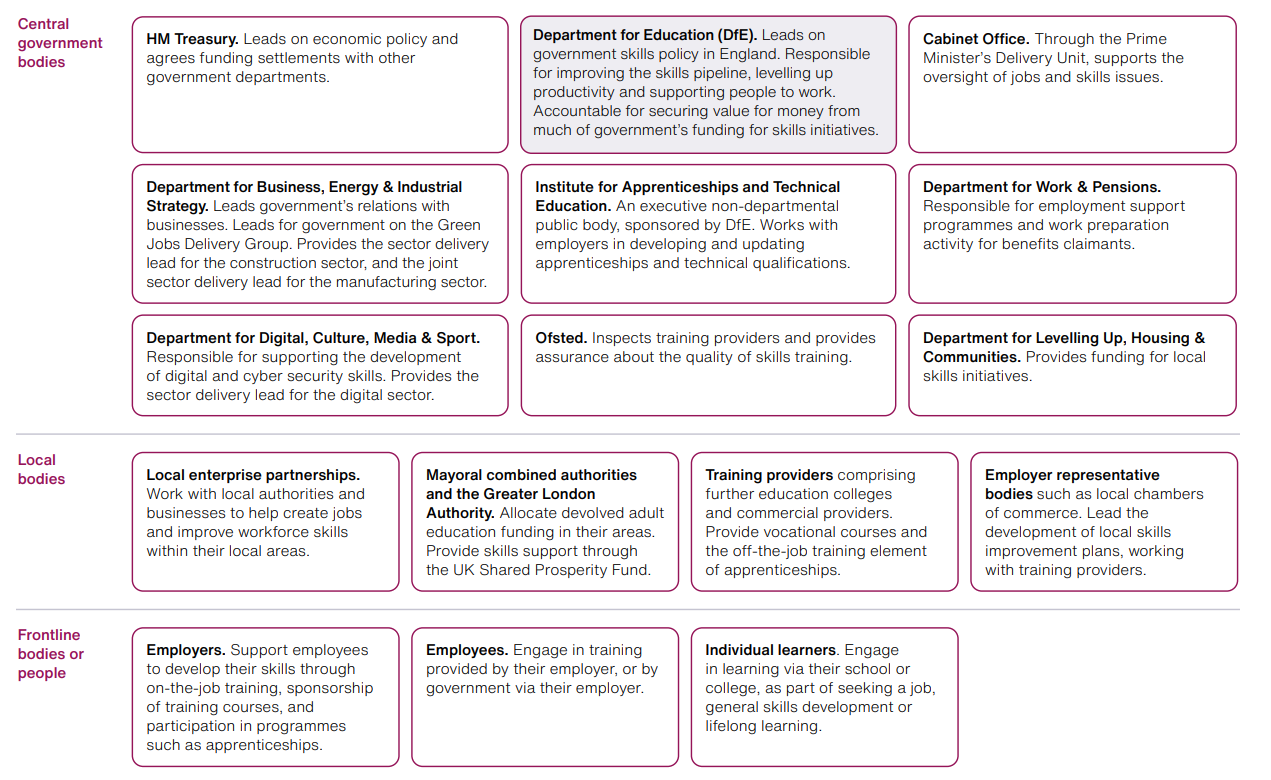

Since then, in England the skills remit has tended to circle the Department for Education (DfE) plughole in ever-tightening circles, but with instructions to share the soap in the bathtub with a whole bunch of government departments, intermediaries and vested-interest bodies. As the National Audit Office (NAO) wrote in 2022:

The skills system [in England] is complex, requiring government departments and other bodies to work together effectively.

Source: Developing workforce skills for a strong economy (NAO, 2022)

In fact, staying with NAO, it’s interesting in a geeky sort of way to compare NAO’s representations of the skills systems in England in 2007 and 2022.

2007

2007: Organisations in partnerships involved in the delivery of the Government’s skills agenda in England (NAO, 2007)

2022

2022: Main bodies involved in developing workforce skills in England (NAO, 2022)

Apart from an obvious difference in style of presentation – perhaps with more of an emphasis in 2007 on how the system works rather than simply what the system is – we can see some notable non-departmental bodies that have either disbanded or been taken into the DfE fold since 2007. Like the Higher Education Funding Council for England – closed 2018 and replaced by Innovate UK (sponsored by Department for Science, Innovation and Technology) and the Office for Students (sponsored by DfE) – and the Learning and Skills Council – abolished in 2010 and replaced by the Skills Funding Agency (which was in turn moved into the DfE as the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA) in 2017) and Young People’s Learning Agency (closed 2012 and also moved to the DfE where it also now sits under ESFA).

While we’re on the subject, going back through time we’ve also seen some other pretty useful skills bodies dissolved: the Work Research Unit (closed 1984), the Manpower Services Commission (closed 1987), and the UK Commission for Employment and Skills (UKCES, closed 2017). In our humble opinion, they have all left gaps.

So, who are we left with as intermediaries, to advise DfE on the skills agenda when it isn’t too busy micro-managing things like T Levels? Well, there’s IfATE, of course, plus the ever-expanding regulator Ofsted. Also the LEPs – oh, hang on, not the LEPs anymore – and the MCA’s. And, two layers removed from Whitehall, we have the rather curiously-named ‘Frontline bodies of people’ – that’s you and us. We refer you to our previous post for an opinion on how that part of it works.

But, it seems to us that the bottom line is this: if NAO had had a go in 2022 to show not just what the English skills spaghetti system is, but also how it works, it’s difficult to see how it might have conceptualised it in the neat way Skills Development Scotland (SDS) has done:

Image: SDS

Why is all this so important? We hardly need say, but we will anyway: the world of work is going through some major changes right now. Digitalisation, automation and in particular AI stand to displace a ton of work, from machinists to paralegals to delivery drivers. Then there’s the green revolution – if revolution it be – that stands to impact all sorts of jobs, from the frontline to the backroom boys and girls. Perhaps more insidiously, the wider labour force is also being impacted by increasing levels of economic inactivity, an ageing workforce, changes in migration flows into and out of the UK, and also the (sometimes rather vague) expectations of those trickling into work from education. So, focus is the key.

There have, of course, been plenty of reviews over the years; we’re good at those. In recent times, the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices (2017) made a few kilogrammes worth of recommendations and duly resulted in the Good Work Plan from BEIS (as was) in 2018.

At the heart of [the] recommendations was an overarching ambition that all work should be fair and decent and for employers to offer opportunities that give individuals realistic scope to develop and progress. We fully share this ambition and set out in the Industrial Strategy the important role quality work can play in boosting UK productivity.

Good Work Plan, BEIS, 2018

In fact, there’s another review of sorts going on right now, this time by an All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) chaired by Matt Warman MP, who wrote to (then PM) Boris Johnson in 2022 calling out skills development as a key focus of future work (the others being AI and automation, place and flexibility, and workers’ rights), and adding that ‘ultimately, it is action, rather than any review, that will prepare the UK economy for future challenges and address the issues facing workers and employers’.

Work will always rightly be shaped by business rather than government – but today there are still a number of barriers that prevent businesses from taking full advantage of opportunities to upskill their workforce and increase productivity. Many workers have yet to see the benefits of 21st century working practices in their own jobs.

Matt Warman MP, 2022,

So, where is this all going? Well, until someone, somewhere in English government actually ‘owns’ work in something approaching the old-style Ministry of Labour way, then it’s difficult to see whither it goes. Certainly, there’s no shortage of good folk calling out the problems with the current system, but there’s nobody really fielding them, collating them and turning them into a shared policy narrative in the way SDS is doing in Scotland. Likewise, there’s a growing body of data on the subject, some of which is being scratched together by DfE’s Unit for Future Skills; but this is far from being comprehensive and to see the bigger picture means building a mashup of commercial data from the likes of Data City and Lightcast, and public data, like ONS and its various surveys on population and the labour force. And it seems that there’s nobody doing any real foresighting, although we have to say we think the Catapults do a reasonable job, albeit within the rather British tendency to focus on Becher’s Brook rather than concentrating on the five other fences that need to be jumped before it.

When it comes to green, the pool becomes even muddier. Granted, we all seem to agree that the net zero transition will bring lots of jobs, and most of them seem likely to be ‘good’. But the Brownian motion on green between HM Gov’s various departments seems to be even more chaotic than that for common or garden work, bringing the Departments for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) as spinouts from the now-disbanded BEIS into the mix, alongside the usual suspects shown in the NAO skills ‘lipstick’ chart we saw earlier.

But, as ever, we remain optimistic. England can do this and, as Sir Michael Barber said to the APPG on the Future of Work last year, with a 10-year strategy in place, it’s just conceivable that dear old Blighty could achieve the same improvements as it did with pre-school education during the late nineties and early noughties. A good place to start might be to reset a tendency we’ve noticed in the skills narrative (is it just us?) to talk about education and skills rather than employment and skills. It’s almost like electricians and plumbers can emerge fully competent from classrooms, instead of learning their trades through a few years of proper on-the-job grind.

Now, surely that could never happen, could it?