Bridging the Green Divide—Just Transitions in a Turbulent Economy

Introducing The Green Edge First Thursday--a deeper dive into our month’s most compelling sustainability read.

Fresh from our Yuletide slumber, we present our inaugural Green Edge First Thursday—yes, yes, we know that today is technically not January’s first Thursday, but our Top Read for this month comes from Scotland, so we discounted the Hogmanay holiday. With that out of the way, let’s get down to talking about this month’s highlight, Prof Dave Reay’s The Uneven Foundations of a Just Transition for Workers: A UK Perspective, published in Frontiers in Climate.

Why did this piece top our list? Because it digs into the messy reality of change. When the economy shifts, it’s not all shiny new opportunities and success stories. There are losers too—people who lose their jobs, whose career prospects vanish. Sometimes entire sectors or specific regions bear the brunt. That’s why understanding the impacts of the green economy and figuring out how to soften the blows is so crucial. On the flip side, new industries and radical transformations in existing ones bring fresh opportunities—but only for those who can access them. Ignore the principles of a just transition, and we risk derailing the whole process.

The Jobs Mirage: Who’s Winning, Who’s Losing?

Not too many years ago the ILO presented us with a sparkling vision of 24 million new jobs globally by 2030. But as the data rolls in to our post-pandemic world, it’s clear that not everyone’s invited to the feast. For the more pessimistic amongst us, it’s tempting to think that for every shiny new position in clean energy, there’s a steelworker or a factory worker somewhere waving a redundancy notice.

Take three examples from the UK: oil refining in Grangemouth, steel production in Port Talbot, and car manufacturing in Luton. In each case, the shift towards a net-zero future has forced businesses to adapt. Oil refineries are evolving to produce sustainable aviation fuels. Steel production is moving to hydrogen-based processes, which require far fewer workers. Meanwhile, the car industry is pivoting from internal combustion engines to electric motors. This isn’t just about swapping one power source for another. It’s a wholesale transformation where mechanical engineering gives way to digital tech, software, and battery innovation.

In our view, The Guardian’s 4th January editorial came as close as it ever does to nailing it: unless the government acts sensitively and decisively, pockets of unemployment could spiral into devastation and resentment—a fertile ground for reactionary forces.

"The politics of this look sadly familiar: every closure, every big job loss will aid those on the right who claim net zero is a zealots’ agenda."

Source: The Guardian

This isn’t a new story, of course. The Redundancy Payments Act of 1956 was designed to cushion the blow of job losses in the car industry. Over time, it inspired initiatives like Resettlement Groups at ICI and British Steel Corporation (Enterprises), which paired redundancy payments with pathways to new careers and local economic regeneration. Similarly, Europe’s coal and textile industries in the 1950s grappled with rapid change, offering lessons in managing sectoral upheaval.

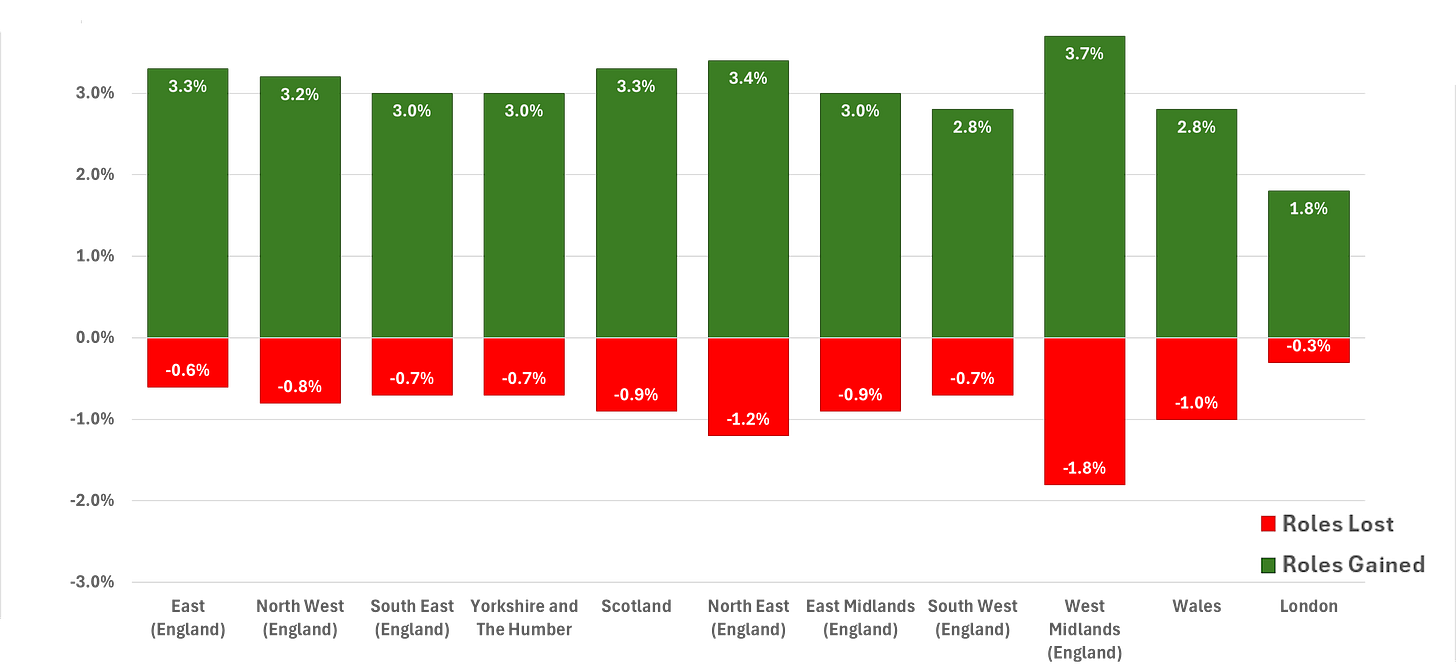

Gross roles by UK region created and lost as percentage of 2021 roles. Image: TGE from ONS/Bain.

We see an uneven impact of the net-zero transition across regions as well as sectors. And Prof Reay’s study argues that workforce projections often highlight headline gains but tend to overlook deeper cracks—gender, ethnicity, and disability biases that could widen, not shrink, in the coming decade. For example, with males dominating the energy and construction sectors, the current outlooks there for inclusivity are bleak. Unless we act, net zero could reinforce, rather than redress, inequality.

“[T]he UK faces a clear risk of perpetuating and further enhancing gender, ethnicity and disability biases in the workforce.”

Source: Reay, D. (2024). The Uneven Foundations of a Just Transition for Workers. Frontiers in Climate.

But a just transition isn’t just about the workplace. Home retrofits, electric vehicle adoption, and heating upgrades—the backbone of domestic decarbonisation—are financially out of reach for many. Low-income households risk being left behind in what amounts to a green divide. Without subsidies and inclusive finance schemes, we risk creating parallel economies: one clean and efficient, the other struggling and sidelined.

Thus far, the UK’s approach is somewhat of a patchwork quilt—but then, that’s how we do things here, don’t we? There’s some good stuff going on, though. As we highlighted in another of our Top Reads this month, Scotland’s Just Transition Commission is focusing on a monitoring framework North of the border that embeds equity into climate policies, tying it to skills through the Climate Emergency Skills Action Plan. Meanwhile, Wales has the Well-being of Future Generations Act, enshrining sustainability and equity in law. The North Sea Transition Authority collaborates with the offshore wind industry, while campaigns aim to broaden access to maritime and energy apprenticeships. Yet marginalised groups often remain on the sidelines.

Other countries may offer lesson too. France, Germany, and the Netherlands have policies addressing just transitions, but hard data on their effectiveness remains elusive. How many people have truly been helped? The numbers are sparse, and the stories are often anecdotal.

The future isn’t set in stone—or hydrogen, for that matter. Prof Reay’s call to action suggests seven key government steps, including mandatory workforce diversity targets and tighter links between climate policies and equality commitments. But policy alone can’t fix a fractured landscape. It’s about partnerships—industry, unions, communities, and educators pulling together.

As we step into 2025, it’s important to remember that transitions aren’t inherently just; they must be made so. Because in the rush for green, we can’t afford to leave anyone in the grey.